In early September 2024, the US Department of Justice announced a set of measures to curb electoral interference in the upcoming presidential election, scheduled to take place two months later.

This was the most significant indication to date that foreign actors were seeking to meddle with the election. In a deeply polarised environment and with the outcome appearing to be on a knife’s edge, there was widespread concern that foreign powers could significantly disrupt the election and affect its result. In the end, Donald Trump’s resounding victory – and the swift acceptance of the result by the Democratic Party – dispelled those concerns.

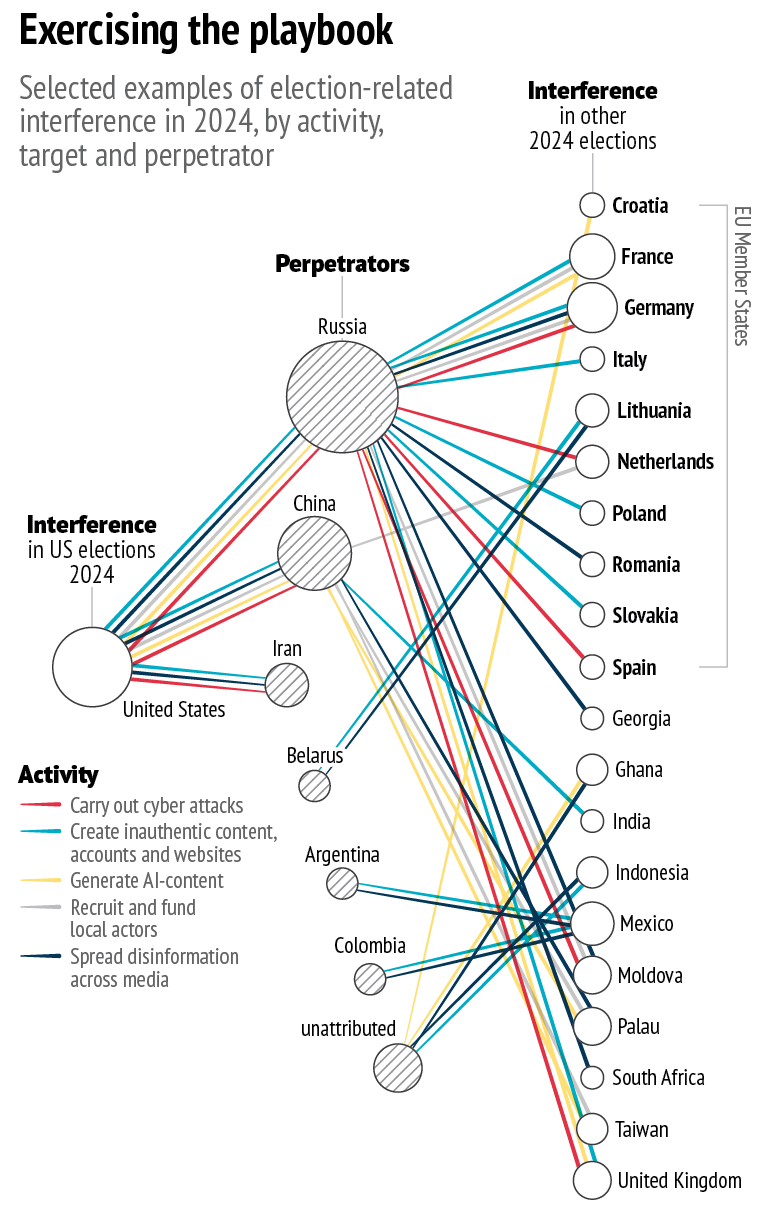

However, this should not serve as an excuse to overlook the significant attempts by foreign powers to influence the democratic process. Strategic rivals are becoming bolder and more astute in their information manipulation and other interference activities. US agencies implemented several measures to respond to these malign actions and prevent disruptions.

Foreign meddling in the run-up to the elections

The US’s three main strategic adversaries – Russia, China and Iran – were all involved in efforts to influence the 2024 election. This was not their first attempt, as Russia interfered in the 2016 election, while China and Iran were active in the 2022 midterms. In 2024, Russia appeared to favour Trump because of the now president-elect’s stance on the war in Ukraine and criticism of NATO. Iran, in contrast, was opposed to Trump’s return due to his past policy of maximum pressure against Tehran. China did not appear to show a preference for either candidate.

Beyond this, all three adversaries agreed on one objective: they wanted to sow chaos and undermine electoral integrity, while creating mistrust within the American electorate. A China-aligned influence operation had the apparent goal to ‘seed doubt and confusion among American voters’. Another group, linked to Iran, also appeared to be ‘laying the groundwork to stoke division in the election’.

These actors also extended their efforts across the Atlantic, aiming to erode trust in American democracy among European publics. An FBI dossier filed in a court affidavit in September included evidence of a Russian operation targeting politicians, businesspeople, journalists and other key figures in Germany, France, Italy and the UK. The messaging sought to undermine the transatlantic relationship, question support to Ukraine and depict the US as untrustworthy.

Back to the AI future

Russia, China and Iran all demonstrated a growing ability to create and disseminate AI-generated media and digital content during the 2024 campaign. In January, a fabricated video depicted President Biden urging New Hampshire voters to abstain from voting in the state’s Democratic primary. Similarly, following Biden’s withdrawal, a deepfake audio of Vice-President Harris appearing to speak incoherently circulated on TikTok. Fake audio clips of Trump mocking Republican voters were also spread. Beyond the US, over 130 deepfakes have been identified in elections worldwide since September 2023.

Allying with local actors

Foreign actors relied on recruiting local influencers, activists, and even commercial companies ahead of the election. As usual, extremist groups used the Russian-owned platform Telegram to spread disinformation. Beyond Telegram, the FBI affidavit outlines Russia’s efforts to secretly fund and promote a network of right-wing influencers: ‘RT had funnelled nearly $10m to conservative US influencers through a local company to produce videos meant to influence the outcome of the US presidential election’. RT employees also sought to hire a US company to produce Russia-friendly content. By outsourcing some of its efforts to commercial firms, Russia seeks to distance itself from the content created.

Fake it till you make it or break it

During the electoral campaign, foreign actors increasingly posed as American citizens. China was especially active in promoting ‘real videos, images and viral posts targeting US culture war issues, primarily from a right-wing perspective’. Topics shared included LGBTQ+ issues, immigration, racism, guns, drugs and crime. The campaign aimed at ‘camouflaging’ China-friendly content as domestic discourse and used ‘spamouflage’ tactics to spread misleading information through inauthentic accounts. Iranian groups created fake websites, impersonating American activists and promoting divisive content.

A plethora of cyber threats

In August, Iran targeted the Trump campaign, stealing a lengthy vetting document on vice-presidential nominee JD Vance and distributing it to media outlets. Iran-linked accounts also sent threatening emails to escalate tensions: since 2022, Democrat-registered voters have received emails from alleged members of the Proud Boys organisation threatening them to ‘vote for Trump or else…’ In a campaign known as ‘Doppelgänger’ Russian hacktivists utilised a wide network of social media accounts to target public opinion. These accounts impersonated legitimate news websites to mislead and confuse, or to spread whistleblower information that had been ignored by the mainstream media. For instance, Russian influence network Stork-1516 promoted a fabricated video in which a teenage girl in a wheelchair claimed that she had been paralysed after a hit-and-run accident involving Harris.

Discussion